Contrary to the idea of a simple “coat of fat,” the survival of marine mammals in Canada’s icy waters is a masterpiece of biological engineering. Every adaptation, from breath-holding oxygen management to the chemical composition of milk, represents an optimized solution to extreme physical challenges—far more complex than simple passive insulation.

Imagining a humpback whale emerging in the icy waters of the St. Lawrence or a seal basking on an Arctic ice floe raises a fundamental question of physiology. How can these warm-blooded creatures, just like us, not only survive but thrive in an environment where the water can border on the freezing point? The most common answer mentions their thick layer of fat, the famous “blubber.” While this layer is essential, it is only the visible part of a much more sophisticated set of solutions—a true arsenal of adaptations forged by millions of years of evolution.

Reducing their survival to a simple matter of insulation would be like admiring a rocket while only talking about its paint. The reality is a symphony of physiological, metabolic, and behavioral adjustments. But then, if the key isn’t just blubber, what is this hidden biological engineering that allows them to defy the laws of thermodynamics? By deconstructing these mechanisms, we discover solutions of staggering efficiency in the face of challenges like thermal conduction, hydrostatic pressure, and hypoxia.

This article offers a deep dive into the world of extreme thermoregulation. We will explore how blubber thickness is just the beginning, how different seal species adopt opposite strategies, and how cetaceans manage dives to crushing depths. We will also see how this science of survival applies to the development of young animals and even inspires our own technologies for facing the Canadian deep cold.

To navigate through these fascinating adaptations, here is an overview of the topics we will cover. This journey will reveal the secrets of these masters of the cold, far beyond common misconceptions.

Summary: Adaptation Strategies of Marine Mammals to Polar Cold

- Why is blubber thickness vital for thermoregulation?

- Harp seal or harbor seal: who stays on the ice in February?

- Prolonged breath-holding: how does the sperm whale dive to 2,000 meters without decompression sickness?

- The fatal mistake of believing a seal pup alone on the ice is abandoned

- Ice kayaking: is it the ultimate way to approach northern wildlife?

- Multi-layer system: which fiber to choose for the base layer at -25°C?

- Grey or white: how to recognize a juvenile beluga from a reproductive adult?

- What is the taiga and why is it so different from the dense boreal forest?

Why is blubber thickness vital for thermoregulation?

The primary challenge for a marine mammal in Canadian waters is heat loss through conduction. Water robs body heat about 25 times faster than air. Faced with this constant energy theft, the first line of defense is exceptional insulation: blubber. But it is not just a simple layer of fat. It is a specialized adipose tissue, an organ in its own right whose structure is optimized to minimize thermal loss. Its efficiency is such that the blubber layer of bowhead whales—the giants of the Arctic— can reach 45 centimeters in thickness, a record documented by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

This efficiency is based on a simple physical principle, as explained by marine mammal specialist Dr. Ann Pabst of the University of North Carolina Wilmington:

Blubber is a thick layer of adipose tissue whose thermal conductivity remains relatively low. This implies that blubber does not transfer heat the way other tissues, such as muscle or skin, do.

– Dr. Ann Pabst, University of North Carolina Wilmington

However, blubber thickness is not uniform across species; it is the result of an evolutionary trade-off. For example, at the end of the feeding season, a bowhead whale can have a fat layer of nearly 50 centimeters. In contrast, a humpback whale, which migrates to warm waters to breed and fasts for months, will only have a layer of about 15 centimeters. This difference illustrates that blubber is not only an insulator but also a crucial energy reserve, the management of which is adapted to each species’ life cycle.

Blubber thus acts as a passive thermal shield, but survival in the cold is also a matter of active strategy, particularly behavioral.

Harp seal or harbor seal: who stays on the ice in February?

While insulation is a universal solution, the strategies for using it vary radically, even between closely related species like the harp seal and the harbor seal. The choice of winter habitat is a striking example of these evolutionary divergences. In February, in the heart of the Canadian winter, only the harp seal will be massively present on the offshore pack ice, notably off Newfoundland and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. It is a pagophilic species—meaning it depends on sea ice, particularly for giving birth. The harp seal population in the Northwest Atlantic numbers more than 7.4 million individuals, forming dense colonies on the ice to reproduce.

The harbor seal, on the other hand, adopts a very different strategy. Less dependent on the pack ice, it prefers coastal areas, estuaries, and rocks, even in winter. It is more solitary and gives birth later in the spring, on dry land. This difference in behavior illustrates two distinct responses to the same environmental problem, each with its advantages and disadvantages, beautifully summarized in the following table.

| Characteristic | Harp Seal | Harbor Seal |

|---|---|---|

| Winter Habitat | Offshore pack ice (Newfoundland Front) | Less icy coastal zones |

| Social Behavior | Vast dense colonies | Solitary or small groups |

| Pupping Period | February-March on the ice | May-June on coastal rocks |

| Ice Dependency | Critical for reproduction | Minimal |

The harp seal has optimized its physiology for life on the pack ice, while the harbor seal has opted for greater habitat flexibility. This divergence shows that survival is not just a question of the “best” adaptation, but of the strategy most consistent with a species’ entire life cycle. For the harp seal, ice is both a nursery and a refuge—a risky bet in the era of climate change.

Beyond the cold, the depths pose an even greater challenge: pressure and the lack of oxygen.

Prolonged breath-holding: how does the sperm whale dive to 2,000 meters without decompression sickness?

Surviving in icy waters is not limited to fighting the cold at the surface. For predators like the sperm whale, it involves dizzying dives into underwater canyons, such as the Gully off Nova Scotia, to hunt giant squid. At 2,000 meters deep, the animal faces pressure 200 times higher than at the surface and total darkness. The feat is all the more remarkable because it is achieved while holding its breath, which can last for over 90 minutes. Survival here relies on physiological engineering geared toward managing pressure and oxygen.

To avoid decompression sickness (the “bends”), which results from the formation of nitrogen bubbles in the blood during a rapid ascent, the sperm whale has a radical solution: it does not breathe underwater. Before diving, it exhales a large portion of the air from its lungs. Then, under the effect of pressure, its flexible rib cage allows its lungs to collapse. Residual air is then confined in reinforced airways where gas exchange with the blood is impossible. No gas in the blood, no bubbles upon ascent.

Oxygen is therefore not stored in the lungs, but massively in the blood and muscles, thanks to very high levels of hemoglobin and myoglobin. During the dive, its heart rate drops drastically (bradycardia) and blood circulation is redirected to feed only vital organs (brain, heart). It is a meticulous management of energy. This set of adaptations allows for feats that defy the imagination, with Cuvier’s beaked whale even having been observed during dives to nearly 3,000 meters deep.

This high-tech engineering must be functional from a very young age, a challenge particularly visible in seals.

The fatal mistake of believing a seal pup alone on the ice is abandoned

Finding a “whitecoat”—a young harp seal with pristine fur—alone on a stretch of ice can trigger a reflex of compassion. Yet, human intervention, even well-intentioned, is often the worst thing to do. This situation is generally not a sign of abandonment, but a normal facet of the species’ mothering strategy, a strategy entirely focused on ultra-rapid energy transfer. The young animal’s survival depends on its ability to develop its own layer of blubber as quickly as possible, and nature has found a formidably efficient solution.

The key is the composition of the mother’s milk. With a fat content that can reach up to 50%, seal milk is one of the richest in the animal kingdom. It is a true energy concentrate that allows the whitecoat to gain up to 2 kilograms per day. During the brief nursing period of about 12 days, the mother must return to the water to feed. It is during these absences, which can last several hours, that the young pup is left alone. It is vital not to approach it, as the presence of humans could prevent the mother from returning.

In Canada, interaction with marine wildlife is strictly regulated. If you find a young seal that seems to be in distress, it is imperative to follow a precise protocol to ensure its safety and yours.

Action Plan: What to do if you find a young seal alone in Canada

- Do not approach: Maintain a minimum distance of 100 meters. A wild animal, even a young one, can be dangerous.

- Observe without intervening: The mother is very likely hunting nearby and will return. Your presence may discourage her.

- Contact the authorities: In Quebec, call the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network at 1-877-7baleine. Elsewhere in Canada, contact the local Fisheries and Oceans Canada office.

- Provide precise information: Note the location (GPS coordinates if possible), describe the apparent condition of the animal (thin, injured, lethargic), and the environment.

- Follow the experts’ instructions: Never attempt to feed, give water to, cover, or move the animal. Only professionals are authorized to intervene.

This necessary distance also raises the question of the best practices for observing this fauna without disturbing it.

Ice kayaking: is it the ultimate way to approach northern wildlife?

The idea of paddling silently amidst the ice, near whales and seals, is the quintessential image of northern ecotourism. Kayaking is often perceived as the most respectful means of approach because it is non-motorized and silent. While this perception is partly true, it overlooks a more complex reality. The absence of engine noise does not mean an absence of disturbance. Marine mammals, equipped with extremely sensitive hearing, perceive sounds we ignore and can be disturbed by the simple presence of a vessel, whatever it may be.

Canadian regulations are very strict on this subject to protect wildlife. In critical areas like the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park, a sanctuary for belugas, the rules are clear: kayakers must maintain a minimum distance of 400 meters from endangered whales. This distance is not arbitrary; it aims to minimize stress and avoid modifying the animals’ natural behavior (feeding, resting, socializing). An approach that is too close, even if silent, can be perceived as a threat and provoke flight, wasting energy precious for survival.

The impact of noise, even low-level noise, is an active area of research, as highlighted in a report from Environment and Climate Change Canada:

We have evidence that Arctic whales will flee from ship noise, sometimes when that noise is barely audible.

– Environment and Climate Change Canada, Marine Mammals in a Changing Arctic Ocean

Ice kayaking can be a magical experience, provided it is practiced with an acute awareness of one’s own impact. The true “ultimate way” is not the one that allows you to get the closest, but the one that guarantees absolute respect for the animal and its vital space. Observation from a distance, with binoculars, is often the most ethical and rewarding practice.

This quest for protection against the cold is not unique to animals; it directly inspires our own technologies.

Multi-layer system: which fiber to choose for the base layer at -25°C?

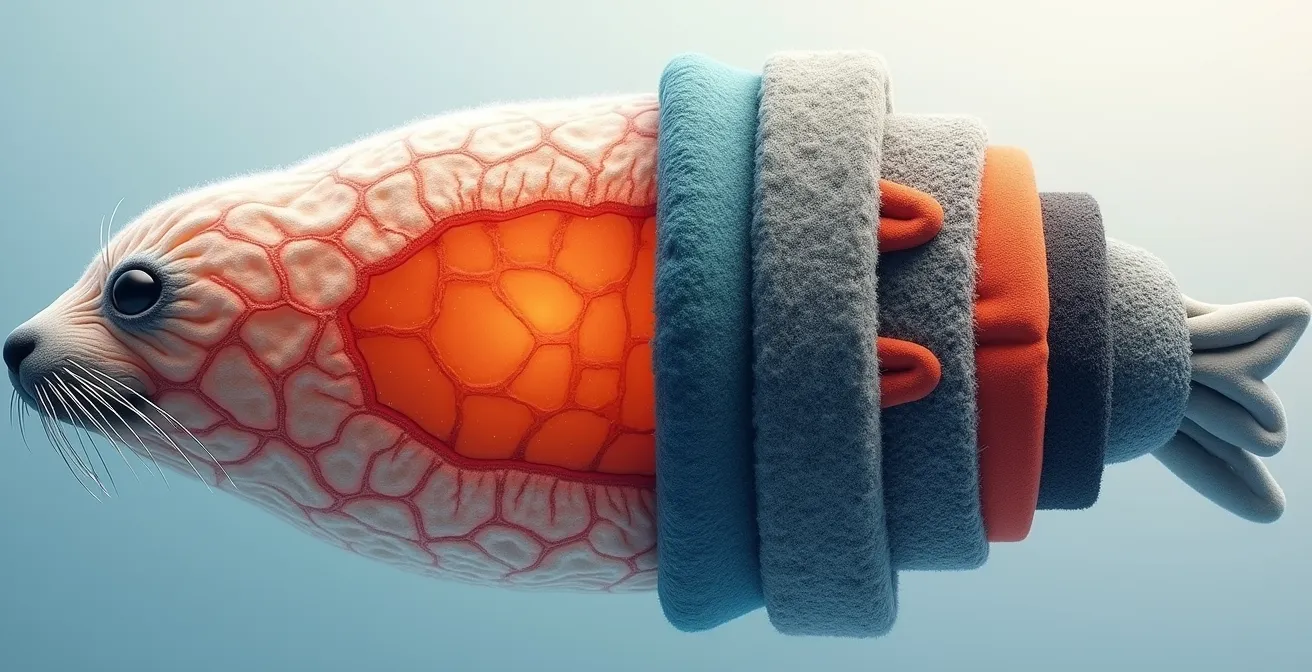

The biological engineering developed by marine mammals to survive the cold offers valuable lessons for humans. This field, known as bio-inspiration, helps us design better technologies. To face a Canadian winter at -25°C, the challenge is similar, though less extreme: how to maintain body heat while managing moisture? The human response, much like that of cetaceans, is not a single thick layer, but an intelligent system. The principle of multi-layer clothing is directly inspired by animal thermoregulation.

The base layer is the most critical. Its function is not to insulate, but to wick sweat away from the skin. Keeping the skin dry is vital, as moisture is a fast track for heat loss. A fiber that retains water, such as cotton, becomes a deadly enemy in extreme cold. The preferred fibers are those that are hydrophobic and transport moisture outward:

- Merino wool: Considered the gold standard, it can absorb up to 30% of its weight in moisture without feeling wet to the touch, while retaining its insulating properties. It is also naturally antibacterial.

- Synthetic fibers (polyester, polypropylene): They are extremely effective at wicking moisture and dry very quickly. They are often more durable and less expensive than merino wool.

This system replicates animal logic: the base layer acts like skin that remains dry, the middle layer (fleece, down) mimics blubber by trapping air for insulation, and the outer layer (shell) protects against wind and water, much like the tough outer skin of a seal. Choosing the right fiber for the base layer is therefore not a detail; it is the foundation of any cold protection system.

These adaptations are not just functional; they are sometimes visible to the naked eye, serving as biological indicators.

Grey or white: how to recognize a juvenile beluga from a reproductive adult?

In the waters of the St. Lawrence or the Arctic, a beluga’s color is much more than a simple aesthetic trait; it is a biological ID card that informs about its age and maturity stage. Contrary to their image as “canaries of the sea” of pure white, belugas are born dark grey, almost brown. This color gradually lightens throughout their youth. They go through a blue-grey tint before becoming completely white. This process is not fast; belugas reach their pristine white color around the age of 12 to 15 years, which approximately coincides with their sexual maturity.

This chromatic transformation is a valuable indicator for researchers studying populations, particularly the endangered St. Lawrence Estuary population. By observing a group, the ratio of young grey individuals to white adults gives a direct estimate of the year’s reproductive success. A large number of “greys” is an encouraging sign, indicating that the population is renewing itself. This is a non-invasive monitoring method used successfully for decades.

In Canada, the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM), based in Tadoussac, is a pioneer in this field. Through photo-identification, its teams track individuals over the long term, using color, but also scars and natural markings, to build genealogies and assess the health of the population. Recognizing a juvenile from an adult is therefore not just an observation game; it is an essential scientific tool for the conservation of an iconic species of Canadian waters.

Finally, the survival of this marine fauna is inseparable from the health of the surrounding terrestrial ecosystems.

Key Takeaways

- Blubber is less a coat than a thermal shield with low conductivity, whose thickness is an evolutionary trade-off between insulation and energy reserve.

- Survival strategies in the cold are diverse: the harp seal depends on the pack ice (specialist strategy) while the harbor seal adapts to the coasts (generalist strategy).

- The biological engineering of marine mammals, from pressure management during dives to milk composition, is so effective that it inspires our own survival technologies (bio-inspiration).

What is the taiga and why is it so different from the dense boreal forest?

To understand the ecosystem of Arctic and subarctic marine mammals, it is impossible to ignore the vast terrestrial biomes that border the coasts. The taiga and the boreal forest, often confused, are actually two distinct environments whose health has a direct impact on the marine environment. The dense boreal forest, found further south, is characterized by tall, tightly packed conifers, such as black spruce and balsam fir, and relatively rich soils. The rivers flowing through it carry nutrients that enrich estuaries, supporting the base of the marine food chain.

The taiga, or lichen forest, represents a more northerly transition zone between the boreal forest and the tundra. Trees there are more sparse, smaller, and the ground is dominated by a carpet of lichens and mosses. It is a more fragile ecosystem, often underpinned by permafrost (permanently frozen ground). The runoff from taiga waters has a different chemical signature than that of the boreal forest, influencing the chemistry of coastal waters where seals and belugas feed.

Finally, the Arctic tundra is a treeless landscape where vegetation is low-growing. This ecosystem is directly linked to marine fauna because it is the hunting ground of the polar bear—a marine mammal that depends on sea ice to hunt seals. The following table synthesizes the characteristics of these Canadian biomes.

| Biome | Characteristics | Impact on Marine Mammals | National Park Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dense Boreal Forest | Dense conifers, rich soils | Rivers feeding coastal estuaries | Gros Morne National Park |

| Taiga (Lichen Forest) | Sparse trees, dominant lichens | Transition zone influencing coastal runoff | Wapusk National Park |

| Arctic Tundra | Low vegetation, permafrost | Direct habitat for polar bears hunting seals | Auyuittuq National Park |

These ecosystems are undergoing significant change. Climate warming is causing a “greening” of the Arctic, where vegetation is becoming more abundant. For example, observations in Nunavik have shown a 30% increase in vegetation in some tundra areas. This change, while seemingly positive, radically modifies the water and nutrient cycle, with consequences for adjacent marine ecosystems that are still poorly understood.

To put this knowledge into practice, the first step is to become a responsible observer. Whether in a kayak or from the shore, respecting distances and knowing who to contact in case of need is not a detail, but an essential gesture for the preservation of these giants and their fragile world.